TV reporter seeks class status in FLSA action against two broadcast groups

During the last week of January 2014, a former television reporter at a station in Portland, Oregon filed a complaint in the Portland Division of the U.S. District Court for the District of Oregon, alleging that he was never paid overtime to which he was entitled under the Fair Labor Standards Act (“FLSA”). His complaint also alleges FLSA retaliation as a distinct cause of action. (Note: the Plaintiff additionally alleges a number of other state causes of action and what appears to be an individual ADA claim, which I will not discuss here). At its root, this suit, and others like it (our firm has raised similar claims on behalf of former media personnel) address the arguable ambiguity in the FLSA over whether a journalist should be “exempt” or “non-exempt”. In the former case, he is not subject to the overtime requirements and may be paid a salary; in the latter case, he must be paid for every hour worked over forty in a given work-week.

You may read the complaint here.

To thumbnail this, the FLSA creates a number of classes of employees who are exempt from the requirements that they be paid overtime. These include commissioned sales employees, computer professionals, drivers, driver’s helpers, loaders and mechanics, farmworkers employed on small farms, salesmen, partsmen and mechanics employed by automobile dealerships, employees at seasonal and recreational establishments, and executive, administrative, professional and outside sales employees. The relevant exemption for the purposes of this case is probably the “professional” exemption which can be practically split into the “learned professional” exemption and the “creative professional” exemption.

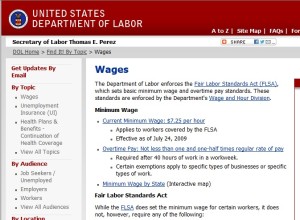

As you can see in the Department of Labor’s white sheet on exemptions for journalists, which I have provided elsewhere on my site, they are typically considered under the “creative professional” exemption. If you look at the requirements for that exemption, you will see that, notwithstanding the salary minimums, a journalist is exempt from the overtime requirements if “the employee’s primary duty is work requiring invention, imagination, originality or talent in a recognized field of artistic or creative endeavor (e.g., the fields of music, acting, writing and the graphic arts), as opposed to routine mental, manual, mechanical or physical work.” Wow. So how does a tv or print reporter fit into that rubric?

Here is some more from that white paper:

[T]he final regulations clarify that employees of newspapers, magazines, television and other media are not exempt creative professionals if they only collect, organize and record information that is routine or already public, or if they do not contribute a unique interpretation or analysis to a news product. For example, reporters who rewrite press releases or who write standard recounts of public information by gathering facts on routine community events are not exempt creative professionals. Reporters whose work products are subject to substantial control by their employer also do not qualify as exempt creative professionals. However, employees may be exempt creative professionals if their primary duty is to perform on the air in radio, television or other electronic media; to conduct investigative interviews; to analyze or interpret public events; to write editorial, opinion columns or other commentary; or to act as a narrator or commentator.

To translate (my take): If you go out and simply cover event-driven news, you are not exempt and are entitled to overtime. By contrast, if you are contributing opinion, are “performing”, or are conducting “investigative interviews” or analysis, an employer may lawfully deny you overtime.

Anyone who has worked in a newsroom should see the problem here: Most reporters chase event-driven stories, but their employers want them to do more. A typical general assignment reporter at a television station should come to a morning editorial meeting with a story pitch that is source-driven and derived from some level of investigation; this is the expectation. In fact, many newsrooms mandate this. In practice, many reporters do not develop sources and wait for an assignment editor to send them to a fire or a homicide, etc.

So what should a media company take away from this? Clearly, it is impractical from an accounting standpoint to create different classes of reporters. To take the position that your reporting staff is non-creative and therefore, non-exempt, exposes you to FLSA liability (as seen in this litigation) and statutory liquidated damages, not to mention that it is, on some fundamental level, disingenuous (how could a news organization, in good faith, claim that its reporting staff never “conducts investigative interviews” and expect to have any credibility in the community?). A number of media companies continue to do this however, and, as typified by this lawsuit and others, are going to have to trek through this clear legal quagmire, at great expense, to find resolution. Alternatively, other media companies have, during the past half-decade, elected to convert their entire reporting staffs to exempt status. This means that once-salaried reporters are now making their salary-plus-overtime and it has surely added significantly to newsroom overtime budgets. It is however, the conservative approach, and may bring certainty that they have controlled their exposure under the Act.

To those companies that have not taken this “conservative” approach, the ambiguity in the statute has created opportunity for plaintiffs. The wrongful classification of an employee may entitle that employee to backpay (unpaid overtime for all hours over 40 worked), liquidated damages and, as argued in this case, punitive damages for alleged retaliation (if you terminate an employee who claims that you fired him for notifying you of the misclassification).

If you worked for one of those media companies that went through a large-scale payroll conversion, you now know why. Here again is a link to the DOL’s position on journalists.